How revolutionary street art tells the ongoing story of Bangladesh’s July Uprising

Words by Rayna Salam

Edited by Armando-Gabriel Chavez

Photography by Ayesha Humayra ChoudhurY and Debashish Chakrabarty

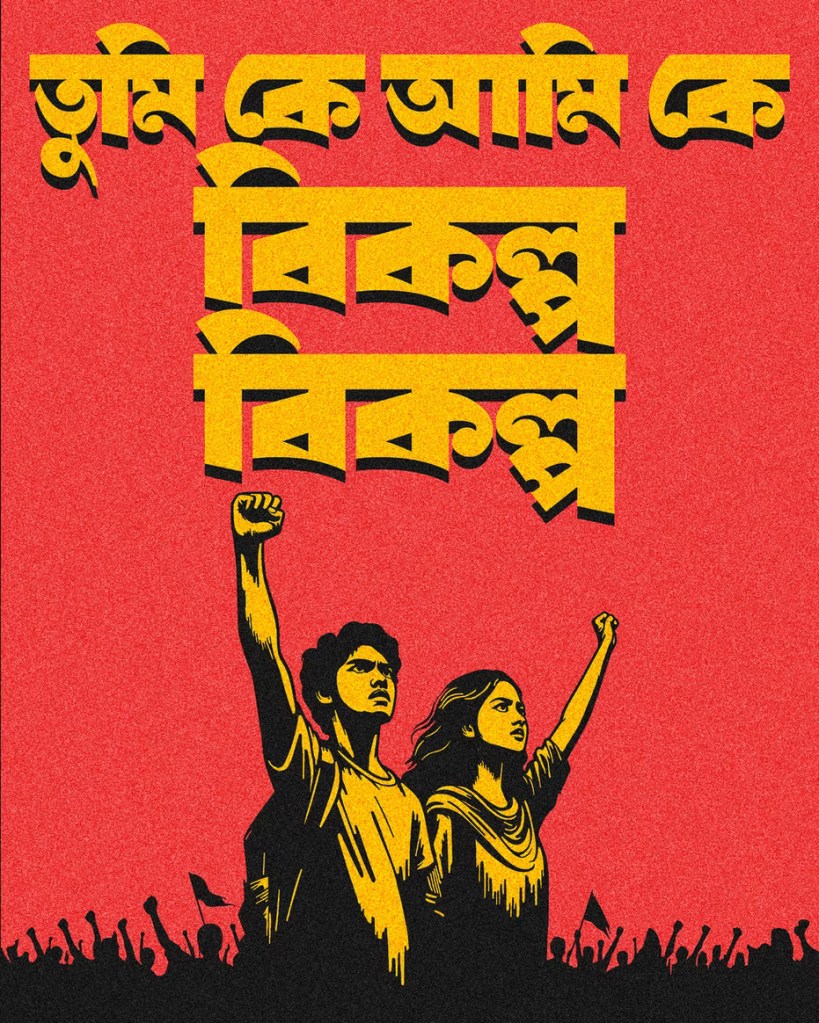

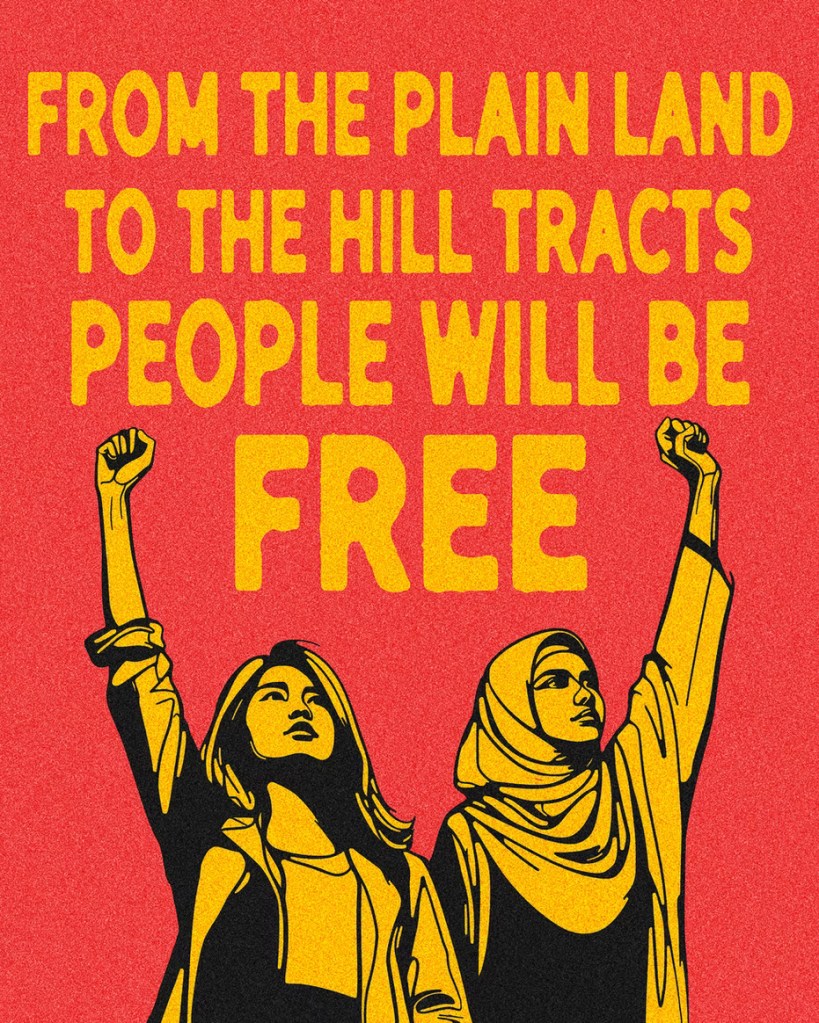

In response to the bloody student-led demonstrations against Bangladesh’s ruling party last summer, U.S.-based artist Debashish Chakrabarty disseminated more than 100 posters illustrating the symbols, martyrs, and demands of the movement on Google Drive—completely for free. Chakrabarty encouraged replication without permission, and diaspora and advocacy groups around the world gathered in public spaces with his prints to express solidarity with the students and their demands. Each poster was designed in a bold, graphic style, with socialist reds and yellows, immediately recognizable as part of the lineage of Bengali political imagery. His style was transliterated by fans and painted anonymously on concrete in the streets around the country. Despite the Awami League government’s military curfew, a nationwide telecommunications blackout, and with Chakrabarty himself thousands of miles away, these red and yellow defiant figures became synonymous with Bangladesh’s historic anti-discrimination student movement.

Graffiti emerged as both a tactic and a proud symbol of the movement that toppled former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s increasingly autocratic fifteen-year tenure. The Bangladeshi government’s history of violently suppressing free expression meant this offline intervention was, in ways, less risky and more accessible than writing online. All one needed was spray paint and a wall.

Emotive, hasty scrawls recount the story of the movement: “We are free 8.5.24,” “killer Hasina,” and “Why did you kill my brothers?” These insurgent, spontaneous messages from last summer live alongside large, colorful murals with future-oriented messaging, painted in the aftermath by organized, student-led campaigns in the wake of the chaos after Hasina’s resignation. Vibrant murals line the walls opposite the Shongshod Bhobon, the sprawling national parliament building that was for a long time, inaccessible to the public. These murals reference Batman, anime-style characters defending democracy, and the slogans of the movement, such as desh ta karo baaper na, or “this country doesn’t belong to anyone’s father.” Other walls have specific demands, such as rights for tea plantation workers and indigenous groups. Others advocate for religious pluralism and secularism—a fraught topic with the proposed constitution reform.

Quick to recognize the importance of graffiti in this movement, archivists and artists immediately began organizing preservation campaigns and exhibitions, commissioning books to capture the living history on the walls before it disappeared. These efforts were both bottom-up and a part of official narratives. Interim leader Mohammed Yunus gifted graffiti photobooks to foreign dignitaries in September, and multinational corporations and the World Bank sponsored exhibitions. In the aftermath of the revolution, Dhaka’s saturated walls bear testament to the ingeniousness of Gen Z and Gen Alpha’s contagious and self-referential meme language, which was able to escape the monitoring of the government.

Of course, the spread of imagery and slogans was not entirely offline. Student organizers broadcast information and instructions on Facebook and Instagram accounts in the buildup to the movement and, as things escalated, cleverly co-opted the government’s language classifying them as razakars “traitors” and criminals into ironic slogans. These same students had learned from previous mobile internet blackouts and protests, using alternate communication methods such as the bluetooth app Bridgefy, Reddit, Discord, and short message services to communicate during the blackout. These tactics are also depicted on the walls.

Above: The idea of “bikolpo,” or an alternative to Hasina, was raised by Hasina’s supporters to assert that there was no other alternative to Awami League rule. In reply, the protestors declared they themselves were the alternative—the people of Bangladesh. Below: Anonymous graffiti artists copied Chakrabarty’s iconic red-and yellow figures from this poster near Dhaka University.

BLOODY JULY

Sheikh Hasina was the longest-serving female head of state in the world. Under her leadership, she transformed her father’s Awami League party into a monolith that became more aligned with her interests than with any national or democratic cause. The last plausibly free election was held in 2008; since then, she has jailed her main opposition leader, banned the third-largest party, expanded draconian “cybersecurity” laws to criminalize free speech, and presided over a violent state apparatus that jailed journalists, minorities, and opposition leaders in secret prisons.

Over the course of Hasina’s fifteen years in office, Bangladesh’s economic outlook grew increasingly dismal. Hasina’s corrupt development projects ended up costing double their proposed cost, and IMF spending restrictions and liberalizing reforms led to the country borrowing heavily from Asian partners, increasing its currency volatility. Despite steady gross domestic product growth and infrastructure investment, nearly everyone was feeling the punishing rate of inflation pushed by the pandemic and war in Ukraine. The middle and working classes were the most affected by the cost of living crisis—the wealthiest 10 percent account for 41 percent of Bangladesh’s total income, and the bottom 10 percent share a little over 1 percent.

The anti-government mass movement began in early July last year, when university students demonstrating for an end to discriminatory civil service quotas were met with unprecedented state violence. The indiscriminate brutality of the response prompted nationwide outrage. The turning point was the murder of Abu Sayeed, a twenty-five-year-old scholarship student from Rangpur. A video of his final moments circulated widely on television news and social media in mid-July: his arms outstretched in front of advancing police, the disbelief on his face once he was shot in the chest, then sprayed with bullets.

Furious, more people joined the students in the streets, and as a result, more videos of state violence against protestors were captured and circulated. It was a fierce, youth-led rejection of extrajudicial torture, police brutality, cronyism, and other gross injustices committed by the Awami League government. After the deaths of hundreds of protestors, including children as young as four, and a five-day nationwide internet shutdown—the longest in the world since the Arab Spring—the public coalesced into one demand: the ousting of the current government. Over 1,400 people died, according to a UN estimate.

The uprising was characterized both by its urban nature and its cross-class, cross-coalition appeal. Private university students in upscale neighborhoods mobilized on the streets in mid-July, directly bringing the urban elite into the fold. No other movement, including the recent 2018 road safety movement, and previous iterations of the quota reform movement, united students this way.

Chakrabarty encouraged replication without permission, and diaspora and advocacy groups around the world gathered in public spaces with his prints to express solidarity with the students and their demands.

Marginalized lower-income urban groups were also key to the success of the movement. Rickshaw pullers gathered in solidarity with the students, blocking the road in front of the Shaheed Minar on August 2. A photograph of a rickshaw puller saluting the marching students is a famous image of solidarity among the memorialized on the walls of the city.

STREET ART AND ITS AFTERLIVES

Even before July 2024, graffiti was a rich, kinetic, and mobile form of expression in Dhaka, wrote Ayesha Rahman Choudhury in her 2021 paper, “Role of Political Graffiti in Recreating Agency in the Public Sphere.” Choudhury brought in the terms dewal likhon and chika mara to describe urban graffiti in the Bangladeshi context. The first literally translates to “wall writing.” The second, chika, means “killing rats” in Bangla—interestingly, there is a subversive element to the second term rooted in activism for national liberation in 1960s East Pakistan. The story goes that when university students were caught doing graffiti outside their dorms, they told police they were out to kill the street rats that were destroying their beds and clothes to avoid detention.

“Chika mara is very specific. You don’t have to make it aesthetic or symbolic, it’s just on the wall, the way you want to say it,” journalist Ayesha Humayra Waresa said, referring to the hurried scrawls that were on the walls in the early stages of the movement this past July, which are now being painted over or crossed out by unknown parties. These include the slogans that spurred the movement on, sometimes unfinished and uncouth: “student killer Hasina,” “murderer Hasina,” or phrases using gendered and misogynistic slurs. Sometimes, they are the target of organized campaigns such as Colours for Reform, who seek to replace it with artwork to promote “social harmony and democratic values.”

Waresa has written extensively on the role of graffiti and rap music during the revolution, and said the vulgar language and “improper” Bangla of these chikas, along with the aggression and anger of rap lyrics, appealed to people of all classes. She said the impulse to remove such language is misguided and classist, pointing out the effectiveness of that form at that time. She believes the spontaneous, passionate feelings in the graffiti should be preserved to remember the stakes of expression.

In December 2024, a satirical image of Hasina’s face with exaggerated, monstrous characteristics was removed from a metro rail pillar near Dhaka University, a historic center of protest and movement organizing. This incited swift protest from student groups. Authorities issued an apology and a new cartoon was drawn.

Oliur Sun, a lecturer at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, agrees with Waresa.“The drive to aestheticize the walls is completely missing out on the fact that you’re erasing history,” Sun said.

Sun wrote an op-ed shortly after the movement on public memory, chika mara, and the erasure of Indigenous voices after the uprising. A part of the students’ dofas (demands) was the demilitarization of the southeastern Chittagong Hill Tracts, where the military and industry have long encroached on indigenous groups such as the Chakma and Marma through tourism, land grabs, and resource extraction. For Sun, the rejection of certain dialects seen as “uncouth” or too foreign reflected the ways Indigenous people were denied their own voice in the outpouring of liberatory political expression. Hasina’s government had long repressed Indigenous film, art, and activism, reflecting an erasure of Indigenous representation that has existed in the constitution since the nation’s founding in 1971.

According to Sun, students in the Hill Tracts found that the slogans and street art symbolizing their oppression have been repeatedly destroyed, even after the movement.

Before last summer, a significant piece of political graffiti was the Subodh/Hobeki series. It drew global attention, with the anonymous artist or group behind it hailed as Bangladesh’s “Banksy.” Stencils of a skinny silhouetted man with unkempt hair and accompanying open-ended one-liners began appearing around Dhaka in 2017 and read “Subodh, run away, there is nothing in your destiny,” and “Subodh is in jail, guilt resides without any worry within people’s hearts.” The man often appeared with the sun in a cage or on his hands and knees. People have interpreted the Subodh series as commentary on the oppressed everyman or day laborer, or even as the conscience of the state.

Notably, Subodh was absent from the July-August 2024 moment until he suddenly reappeared in March of this year outside Dhaka in Chittagong, the second-largest city in Bangladesh. This artwork depicts a statue of Rodin’s “The Thinker” atop a donkey. Sun said it seems to suggest that despite the political imagination and insight of intellectuals, the country, driven by forces outside its control, is going nowhere .

BANGLADESH IN THE INTERIM

There are competing preservationist and reformist forces over revolutionary art in urban space, and these impulses are being contested and questioned. At the same time, the interim government is struggling with a host of issues before the next election in 2026.

There have been several news storms since July: an India-led disinformation campaign about increased attacks against minorities in Bangladesh—which did occur, but were greatly exaggerated—retributory attacks against Awami League leaders and its student wing, and continued persecution of journalists. The interim government pledged to repeal the previous government’s Cyber Security Act, but upheld some of the act’s problematic language, such as a provision on “hurting religious sentiment,” which was used to persecute free expression under the guise of religion.

Meanwhile, the economic situation has worsened. The public has limited information on the specifics of the interim government’s reforms process; commissions on topics such as banking and the constitution were formed, but their goals are unclear, and the government line is that all meaningful reforms take time. Military and business stakeholders are pressuring the government for an election as soon as possible.

There is some intellectual debate about whether to characterize the movement as an uprising or a revolution. Bangladesh has had a continual history of anti-authoritarian movements, but this is the first time a sitting government has been ousted. Now, more than half a year later, many competing interest groups are coalescing to preserve the status quo. This exists around an interesting tension within the revolutionary possibility that still lives in the art on the walls.

It is both the desperate slogans and the beautiful collaborative murals painted after Sheikh Hasina fled the country that tell the story of this urban revolution and how it should be remembered. Contradictory narratives build on one another and form a palimpsest on city walls, tracing a rough post-revolution timeline as the future looks increasingly uncertain.

Rayna Salam is a writer-editor from Bangladesh interested in politics and culture. She maintains compulsive lists—both digital and analog.